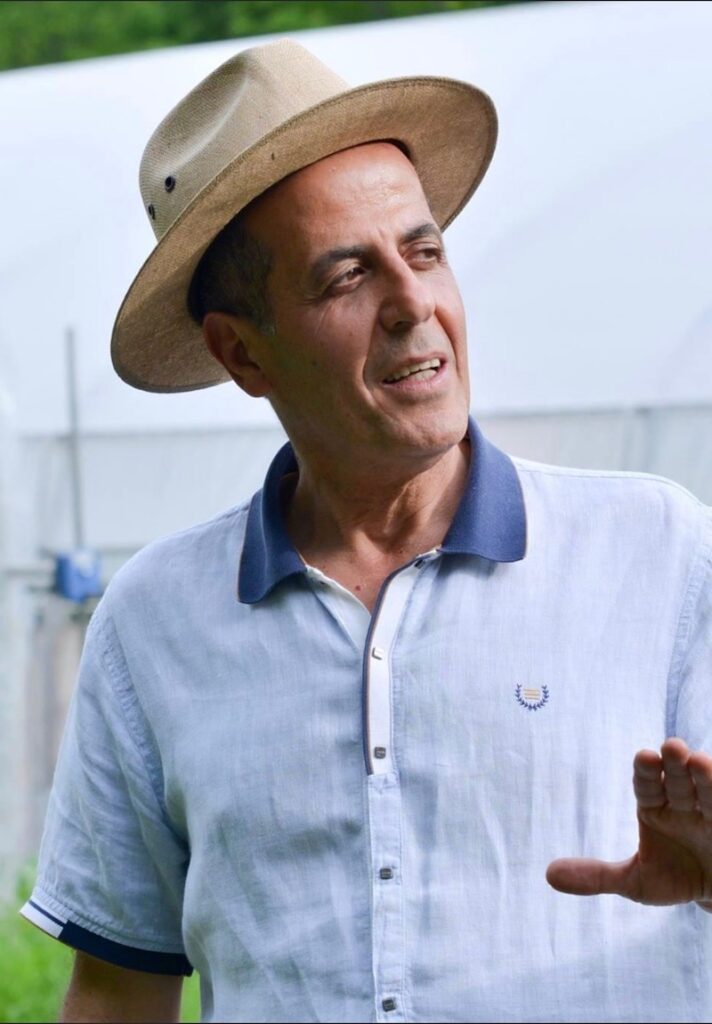

After a 25-year career in the financial sector, organic farmer Ramzy Kassouf is practicing wholistic agriculture to benefit people and the environment.

Is it possible to change the world, one organic farm at a time? Ramzy Kassouf thinks so.

“I’m bullish on humanity,” he says, using a turn of phrase that recalls his former métier as an institutional equities trader.

Now a farmer of organic crops in Senneville, Mr. Kassouf is driven by a passion for community development—to ensure that his farm supplies not only restaurants and stores, but serves local families and food banks, too. Leaving a position in high finance to till the soil is an unusual career change, but for this farmer it was a calling.

His career in the financial sector was serendipitous. “I left Lebanon in 1975 to study engineering at l’Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal,” he says. “In 1979, I had a summer job working as a runner at the Montreal Stock Exchange.” It kick-started his career and led him to take the Canadian Securities Course and to study economics at McGill before moving into the brokerage industry and climbing the ranks. For the following two decades, Mr. Kassouf worked in a series of investment firms—becoming a partner in one—before deciding in 2007 that what he really wanted to do was raise organic crops.

“I had moved to Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue and fell in love with the area,” he says. “I got married and lived there before moving to Baie d’Urfé.”

In 1996—when the real estate market was in a slump—he bought a 30-acre tract of land in Senneville. “It had been farmed by the Legault family until the 1970s, but it was abandoned,” he says. “The land was flooded because a stream that ran through it was blocked in various places by fallen trees. I had bought the land for my retirement and began to think about farming it. It’s zoned agricultural, so the only way it could be used would be as a farm, to take it back to what was intended.”

In 2007, Mr. Kassouf was ready to leave the financial sector. “I knew I needed to do something else. I’d been working but my work was adding nothing to the social fabric or building the socio-economic prosperity of my community,” he says. “So I cut my ties to the financial industry and sold my assets.”

Then he turned his attention to the farmland that he was reclaiming from the flooded creek. However, his lack of agricultural training soon became apparent. “I started by planting an apple orchard, but the local deer ate all the fruit,” he says.

He also had an epiphany. “I was working so hard and realized that farmers are not paid fairly for growing our food. The food system is treated as a commodity that has no relationship to the soil, to the community, to our health. I decided I wanted to farm but I knew nothing about how to do it.”

So Mr. Kassouf became an apprentice at Ferme du Zéphyr, a local organic farm, where he exchanged his expertise in sales and marketing for training in organic agriculture. There, he met two other apprentices and the three teamed up in a business partnership in 2010 to create an organic farm on the Senneville land he had bought. One left the partnership but partner Alex Flores has stayed on.

The land was developed into Les Jardins Carya. The term “Carya” is the botanical Latin name for the hickory tree, which is plentiful in the West Island.

The farm has evolved in the past 12 years to include five greenhouses—two of which are 200 feet long—and a barn where produce is packaged for shipping. The greenhouses produce a variety of vegetables from March to November, while an open field is used to cultivate lettuces during the growing season. “At the beginning, we grew everything,” Mr. Kassouf says. “There were 70 crops in the first five years, and because we were so diversified, we offered community-supported-agriculture baskets and sold our goods at a farmer’s market in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue. Then we started growing for the wholesale market, supplying restaurants, supermarkets and hotels. We still sell to the public at the Ste-Anne Market on Saturdays.”

The number of crops has since been streamlined to 20. And because all of the production is organic, Mr. Kassouf employs the traditional system of crop rotation and the sowing of such cover crops as buckwheat to fix nitrogen levels in the soil. “You cannot survive by skipping this process,” he says. “It’s a long-term 15-year cycle. Amending the soil and taking care of its health ensures that the plants are strong and immune to pests.”

Carya now boasts three farms. An indoor growing facility in Kirkland specializes in microgreens. A third farm—Ferme Biopol in Sainte-Marthe—is a partnership with other farmers.

The month of March represents what Mr. Kassouf calls one of the “shoulder seasons.” Seedlings are started in the greenhouses for the spring weather ahead.

However, Carya’s mission far transcends the production of vegetables. The three farms employ 29 people, many of them university students who work during the summer growing season. And the business recently became a locus for other farmers in surrounding areas who want to get their products to market without selling through distributors. “I am creating a network for the farmers so there is no middleman,” Mr. Kassouf says. “I want the money to go directly to the farmers. Carya is taking care of the logistics to get produce to wholesalers without middlemen. We want to have a major impact on the food system in such a way that it’s equitable to farmers and ecological for the environment.

This former equities trader says he’s also bullish on creating a new way of practicing agriculture. “I don’t want to waste time saving an old process of disintegration that is cancerous,” he says. “I want to build a new institution. There are millions of people who think this way. I’d like to give hope to mankind.”

It’s a good thing to be bullish about.

Lettuces are cultivated in the vast open field at Les Jardins Carya. The mesh coverings are used to protect the young seedlings from marauding deer, the populations of which are plentiful in the wooded areas surrounding the farm.