Obtaining a certificate of location is a necessary step when buying or selling a home, particularly if changes have been made to the property.

It’s no secret that the process of buying a house—especially for first-time buyers—can be stressful. There are steps and details that may be unfamiliar to real estate newbies.

Consider the certificate of location, which is an essential step in the house-buying process. It may seem counterintuitive to survey a property that has existed in a developed neighbourhood for many decades. After all, land and houses don’t move. But properties change over time as they’re modified by structures, says Lawrence Rabin, a professional Quebec land surveyor, who works throughout the greater Montreal area.

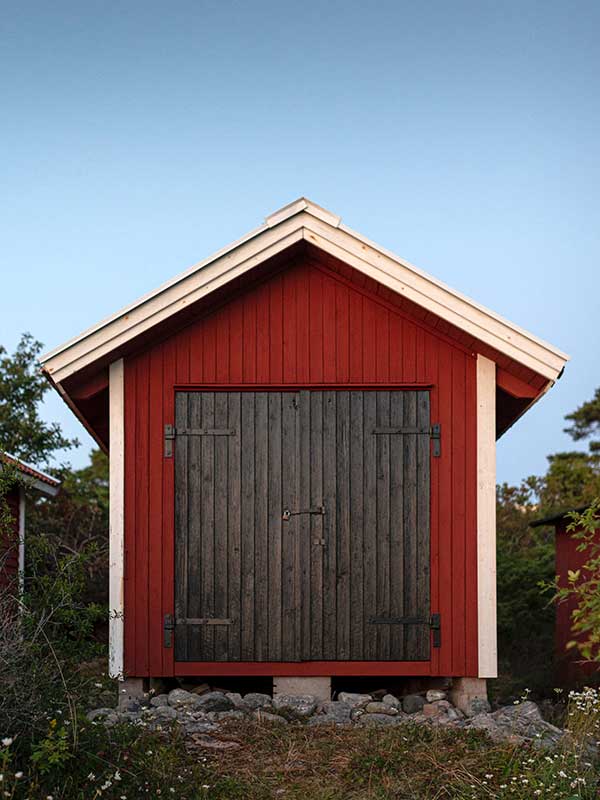

“Surveyors are public officers,” Mr. Rabin says. “We’re there to protect the public by making sure that all the pieces fit together.” That’s “pieces,” as in fences, swimming pools, cabanas, decks, hot tubs, garden sheds, houses and, of course, property boundaries.

“There are different kinds of surveys, but the kind that homeowners need for a transfer of ownership of a house is a certificate of location,” Mr. Rabin says, adding that a new survey should be done for a home-sale transaction if the last one took place more than five or, sometimes, 10 years ago, or if there has been a change to the property.

Quebec’s original cadastral register was drafted in 1866, but was out-of-date when the government began renovating the cadastre in a province-wide plan during the early 1990s.

Have you ever seen surveyors using an electronic distance-measuring device? They’re taking measurements with a laser that gauges distance to within a millimetre. “Every property and construction site is individual,” Mr. Rabin says. “The setback regulations are different everywhere, so we deal with the bylaws of each municipality as well as Quebec’s Civil Code. When a property is being sold, the buyer, real estate broker, vendor, notary and mortgage company need to ensure that there is clear title to it. We examine the property title deeds and not only for the home in question, but for the neighbouring properties as well.”

What could possibly go wrong? Plenty, says Mr. Rabin. Homeowners often install structures on their properties—fences, swimming pools, sheds, hot tubs, accessory buildings, for instance—without getting a municipal permit. They may be unaware of setbacks and utility servitudes. “Sometimes, people install structures without doing their research,” he says. “We may find that a pool or hot tub is under a power line or situated on a zone of non-construction that’s in favour of a Bell, Hydro or Gaz servitude, for example. If that hydro wire falls into a pool or spa, it can cause electrocution. We’re always looking for the what-if scenario.”

Then there’s the question of acquired rights. “It’s not a perfect world and, more often than not, a fence or retaining wall can be encroaching. According to Article 929 of the Quebec Civil Code, a possessor starts to benefit from an acquired right after one year and one day. And according to Article 2918 of the Civil Code, a possessor may benefit from an acquired right after 10 years with a court judgment,” he says.

A property may also be in a zone that is prone to flooding or to landslides. A survey should reveal this, Mr. Rabin says.

In the years that he’s been working as a surveyor, Mr. Rabin has seen plenty of disagreements between neighbours over their property boundaries. “Between 30 and 35 per cent of the surveys we perform turn up problematic for the landowner,” he says. “The dimensions cited on a title deed are sometimes different from what we find in the field.”

He is called to perform mediations between neighbours over disputed boundaries. He’s also been called as an expert witness in court cases when boundary disputes cannot be settled through mediation and end up in litigation. Ideally, he says, the best way to settle such disputes is without resorting to expensive legal solutions.

A professionally done property boundary survey, Mr. Rabin says, “is a form of protection. I tell my clients that they’re protecting their rights. And if you don’t protect them, you may lose them.”